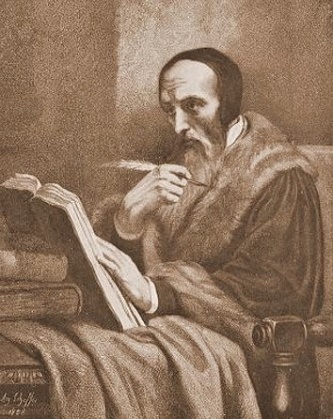

JOHN CALVIN, 1509-1564, Concluded

The first part of our John Calvin discussion can be found in our July post from the Reformation – 500th anniversary series.

Guillaume Farel (1489-1565) invited John Calvin to Geneva in 1536. The church sorely needed guidance and leadership. Calvin was first described in Geneva civil records as a “lecturer in holy Scripture.” Early in 1537 his articles composed to govern the church of Geneva were presented. Included in the articles was direction concerning the practice of the Lord’s supper and the associated use of excommunication. Other articles included the importance of instructing children, the need for elders, the importance of singing Psalms, and a twenty-one-article confession of faith which all who joined the church had to affirm. Calvin, Farel, and other pastors believed that one could not take the Lord’s Supper without affirming the confession of faith, but the Geneva government, as represented in its council, disagreed and said all should be able to partake regardless. This tension between the state and the church led to ordering Calvin and Farel to leave Geneva in April 1538. The history of the church is often a history of the confusion of church and state and the council’s ejection of ministers is an example of such a conflict. When the state and church come into conflict, the state inevitably wields its sword against the church.

Calvin needed to find another place to minister and his first choice was Basel, but a group in Strasbourg under the leadership of Martin Bucer (1491-1551) redirected him to their city. He delivered his first sermon on September 8, 1838. Bucer was senior to Calvin by almost twenty years and his influence was much like a father to his son. But Calvin was able to take Bucer’s ideas, particularly about church polity and the Lord’s Supper, express them in writing more clearly than Bucer could, and then apply them in an organized way. While in Strasbourg, Calvin married Idelette de Bure who had been widowed when her husband died of the plague. She had several children which Calvin took in as his own. During his three years in Strasbourg the political situation in Geneva changed and Farel was imploring him to return, but Calvin did not want to go. However, in the fall of 1540 he gave in saying, “If I had any choice I would rather do anything than give in to you in this matter, but since I remember that I no longer belong to myself, I offer my heart to God as a sacrifice.”

Just a month after his reticent return to Geneva, John Calvin’s ecclesiastical ordinances were adopted by the city government. Included in the document was Calvin’s four church offices—pastor, teacher, elder, and deacon. Calvin and the pastors would at times experience a difficult relationship with the councils as the ordinances and other aspects of the church were applied. The government wanted to retain control over the church and its practices, but Calvin believed the particularly Pauline principle that the state’s ministry was to punish evil doers and protect its citizens, while the church’s ministry was to preach the gospel and administer spiritual discipline. Needless to say, Calvin and his company of pastors sometimes found themselves differing with the Geneva government regarding its authority.

In April 1549, Pastor Calvin suffered an immeasurable loss. His wife of less than a decade, Idelette, died from an extended illness. Calvin was a man who rarely expressed himself about his personal life, but he confided to mentor and friend Pierre Viret regarding the great loss caused by her passing.

Although the death of my wife has been exceedingly painful to me, I subdue my grief as well as I can.… I have been bereaved of the best companion of my life, of one who shared my poverty, but also, if it had been so ordered, would have joined me in death. During her life she was the faithful helper of my ministry. From her I never experienced the slightest hindrance. She was never a burden to me throughout the entire course of her illness.

And to his mentor and friend Guillaume Farel, Calvin also expressed his sorrow.

Intelligence of my wife’s death has perhaps reached you before now. I do what I can to keep myself from being overwhelmed with grief. My friends also leave nothing undone that may administer relief to my mental suffering.… I at present control my sorrow so that my duties may not be interfered with.

A true expression of love and loss by a man who is sometimes described by social historians as a callous and doctrinaire tyrant. Earlier in their marriage, Idelette had given birth to a child named Jacques who died a few days later. Calvin did not remarry.

John Calvin died in 1564 at the age of fifty-four. Theodore Beza, his good friend and biographer, notes that Calvin stipulated he was to be buried in an unmarked grave because he feared his burial site might become an idol. Calvin’s ministry in Geneva was not an easy one because he suffered persecution and insults from some citizens. In his letters he comments that someone had left what appeared to be bodily fluid on the door handle of his home during a time of plague intending to cause his death. Some unhappy residents of Geneva chose to name their dogs, cows, or other animals “Calvin” as insults. Then there were problems during worship. One man took his hunting firearm and dog to church so he could quickly stalk his prey after the service. During a Lord’s Supper service one mentally disturbed woman barked like a dog. A woman used a stool as a weapon to severely injure another woman during an argument over seating, and one woman insisted on sitting near a particular man because she believed that God had told her she would marry him. It was not uncommon for congregants to snore loudly, hold conversations, or pass around food during services. Maybe preachers today should be grateful for their attentive, or at least apparently attentive, flocks during the delivery of their sermons.

John Calvin’s legacy is immense. Much of his teaching became the cornerstone of Reformed theology. Even the United States can trace the organization of its national government to Calvin’s concern for separating church and state. He wrote commentaries on the Bible for much of the New Testament and a considerable portion of the Old. Many of his letters have been published. His Institutes of the Christian Religion came out in several editions from 1536 to 1560 in either Latin or French and it was first translated into English in 1561. Calvin did not personally publish his sermons, but they were copied by a stenographer as delivered and then compiled for posterity. Some sermons are available in English.

On a personal note, whenever I read anything by Calvin, I find myself nodding my head in affirmation as I read a particularly helpful comment. The breadth and depth of his knowledge included not only theology, ecclesiology, Bible, and ministry, but also science, politics, world affairs, law, and just about any subject that could be studied in the day. If the effort is made, the reward from reading Calvin can be considerable. God in his providence has often provided leadership for his church via sprinkling gifted and prolific individuals throughout history who produced written wisdom for successive generations, one of those individuals was John Calvin.

Trackback from your site.