The Reformation – What of it?

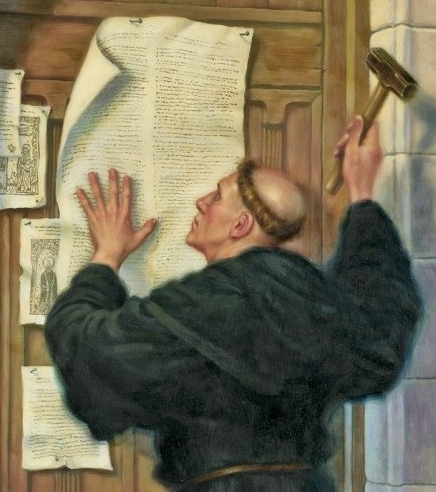

October 31, 2017 will mark the quincentennial of the Reformation. In 1517, Martin Luther posted his Ninety-Five Theses contending with the sale of indulgences by the papacy. The words, “theses,” “indulgences,” and “papacy,” seem out of place today and an Augustinian monk with an odd haircut wearing a garment resembling a bathrobe is certainly not stylish. Besides, how could he have “posted” his Theses, he did not have electricity much less social media? However, in his day the bulletin board for religious issues was the local church door, so Luther used a low-tech hammer and tacks to post the theses to the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg, Germany. This action by Luther which is considered the start of the Reformation led to the founding of denominations including not only the Lutherans but also the Presbyterians, Reformed, and Anglicans. In order to better understand the importance of the Reformation, over the course of the next year, monthly articles explaining its significance will be posted—in the modern sense, on the church website, not the church door. These studies will include history, theology, biography, church government, and confessional information that will work together to answer the question, “What of it, what of the Reformation?”

October 31, 2017 will mark the quincentennial of the Reformation. In 1517, Martin Luther posted his Ninety-Five Theses contending with the sale of indulgences by the papacy. The words, “theses,” “indulgences,” and “papacy,” seem out of place today and an Augustinian monk with an odd haircut wearing a garment resembling a bathrobe is certainly not stylish. Besides, how could he have “posted” his Theses, he did not have electricity much less social media? However, in his day the bulletin board for religious issues was the local church door, so Luther used a low-tech hammer and tacks to post the theses to the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg, Germany. This action by Luther which is considered the start of the Reformation led to the founding of denominations including not only the Lutherans but also the Presbyterians, Reformed, and Anglicans. In order to better understand the importance of the Reformation, over the course of the next year, monthly articles explaining its significance will be posted—in the modern sense, on the church website, not the church door. These studies will include history, theology, biography, church government, and confessional information that will work together to answer the question, “What of it, what of the Reformation?”

At the beginning of the sixteenth century, not only Christianity but all of western Europe revolved around the Roman Catholic Church. It may be difficult to understand in our day of anti-church thinking and separation of church and state carried to excess, but for centuries, for better or for worse, the Roman Catholic Church ruled. It was said during the days of the Roman Empire that all roads led to Rome, so it could well be said that all church roads led to Rome at the dawn of the Reformation. Having the church at the center of life should be a good thing, but there were problems that had developed through centuries of religious monopoly, misuse of power, burgeoning wealth, and unrestrained administrative and clerical growth. The church had become a political entity such that there was a disturbing confusion of church and state. Rulers of the nations and all in positions of secular authority were expected to obey the church and yield to its commands without question. A few examples of the difficulties at the time will illustrate the significance of Catholicism at the time of the Reformation.

First, there were a number of individuals of church history that were recognized by the Catholic Church as saints. A saint was one whose piety and good works were deemed exemplary by the papacy, was worthy of special recognition, and should be venerated. For example, names such as St. Augustine, St. Dominic, or St. Jerome may be familiar to readers. The theological problems of such teaching aside, the length of the list of saints had grown to such a length that special days for their veneration added to other holy days made for many religious holidays. On these days parishioners did not work but were instead involved in special celebrations and other church-centered activities. There were so many of these days that it affected the commerce and economy of the time. Thus, if one has the day off to remember a saint, then one cannot be cobbling shoes for local feet, coopering pails for milking the cows, or weaving wool into winter attire.

Second, there was the problem of the considerable amount of real estate owned by the church. The church was the largest landowner in Europe with mega acres of ground and mega tons of buildings. For example, London’s old walled city occupied about a square mile. For comparison, the area in Greenville bounded by North Pleasantburg, I-385, Haywood, and Laurens Road is a little bit larger than a square mile (mostly the Downtown Airport). Within London’s walls there were just over 100 churches for a population of about 60,000 and every single church was Roman Catholic. Added to the church buildings were schools, monasteries, religious sites, and clerical residences. The church was, in modern terminology, a real estate mogul.

Third, the church employed a considerable number of people and they all had to be paid. For example, there were somewhere between 700 and 900 priests in London circa 1520 and they all had to be housed and fed. Added to the priests were monastics, teachers, mendicants (such as Franciscans, Dominicans, and Carmelites who begged for alms), nuns, and supporting personnel. It has been estimated that up to ten percent of the population in some areas were employed by the church. Not only were there local religious employees, but there were also the bishops, archbishops, cardinals, and other overseers all the way up to the pope himself. The wealth of the church was considerable.

With so many bills and people to pay, how did the church acquire the funds? Again, to London for an example. The church collected tithes but the tithe was not necessarily a tenth. In rural areas a portion of crops harvested was accepted, but in the city, parishioners were taxed by paying a percentage of their rent, or if their homes were owned they paid a percentage of the fair rental values. The church also charged fees for weddings, the Mass, baptisms, burials, prayer in some special cases, and celebratory feasts. Some, note some and not all, local priests took advantage of their flocks and would have their own fees set for duties that did not warrant payment officially. A person in that day could not walk far down the street of a city of any size without seeing something of the church whether it be property or person, and if one encountered a person it might very well be a mendicant begging alms.

However, the proportions, prosperity, power, personnel, and presence of the Catholic Church, or what might be called its temporal and practical issues, were really symptoms of a more serious and fundamental issue—doctrine. The church was the interpreter of Scripture—there were no alternatives. The popes were, and still are, viewed as having their authority by successively occupying the chair of the Apostle Peter and serving as the vicar of Christ (i. e. representative of Christ). In some cases over the centuries of its history, the church, in order to maintain unity and peace, adopted or modified dissenting views as its own when it could do so while being consistent with its position as the interpreter of Scripture. There have been a great number of church fathers and theologians over the centuries that contributed to the development of Catholic doctrine, but as each point of theology was debated, the papacy then set forth the understanding.

Martin Luther and his reforming contemporaries responded to the doctrinal status quo of Catholicism with the five building blocks of reform called the five solas—sola Scriptura (Scripture alone), solus Christus (Christ alone), sola fide (faith alone), sola gratia (grace alone), and soli Deo gloria (glory to God alone). The cornerstone of this five-block structure is sola Scriptura because the Bible reveals all that is needed for one to know God through plumbing its depths and riches. The foundational nature of sola Scriptura is exemplified in the Westminster Confession of Faith, which is the summary of doctrine used by the Presbyterian Church in America. The first chapter, “Of the Holy Scripture,” expresses the foundational importance of sola Scriptura for the theology expressed in the thirty-two chapters that follow. The other four solas as well as other theology, including the hinge-pin doctrine of justification by faith, were drawn by reformers from the well of the Word.

Some of the terminology, ideas, and people mentioned in this first article will be explained in the posts that will follow. The article for February will present the financial-political-social-educational context in which the Reformation occurred. It is important to understand how people lived and thought, the difficulties they faced, the work they did, and how they understood God and the gospel as they were confronted with the teaching of the Reformation.

Trackback from your site.